Becker Muscular Dystrophy (BMD)

Causes/Inheritance

Cause of Becker muscular dystrophy

Cause of Becker muscular dystrophy

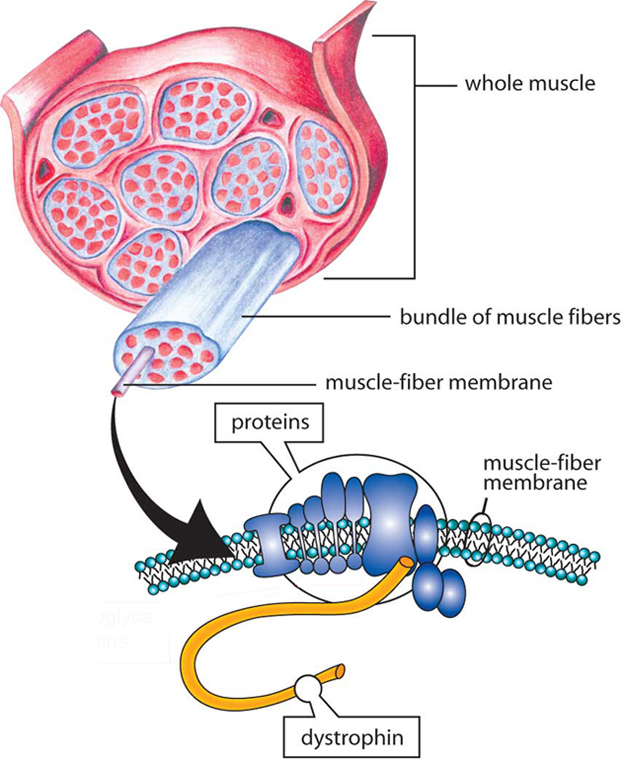

In 1986, MDA-supported researchers identified the gene that, when flawed, or mutated, causes both Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophies (BMD and DMD, respectively). In most patients diagnosed with BMD (65% to 70% of cases), one or more exons (segments of DNA) are deleted.1 However, partial gene duplication has been reported in 5% to 10% of cases.1,2 In 1987, the protein associated with this gene was identified and named dystrophin.

Genes contain codes, or recipes, for proteins, which are important biological components in all forms of life. BMD occurs when the dystrophin (DMD) gene on the X chromosome is altered, thus failing to make sufficient levels of functional dystrophin. Furthermore, dystrophin produced by muscle cells of patients with BMD is structurally abnormal, which leads to abnormal functioning as well. Dystrophin plays a role in keeping muscle cells intact; lack of dystrophin causes muscle cells to be fragile and easily damaged.

In BMD, dystrophin is produced, but its shortened form is only partially functional. Because of the partially functional dystrophin, muscles don't degenerate as badly or quickly as they do in patients diagnosed with DMD, who don’t produce functional dystrophin at all.

Inheritance in BMD

BMD can run in a family, even if only one person in the biological family has it. This is because of the different ways in which genetic diseases are inherited.

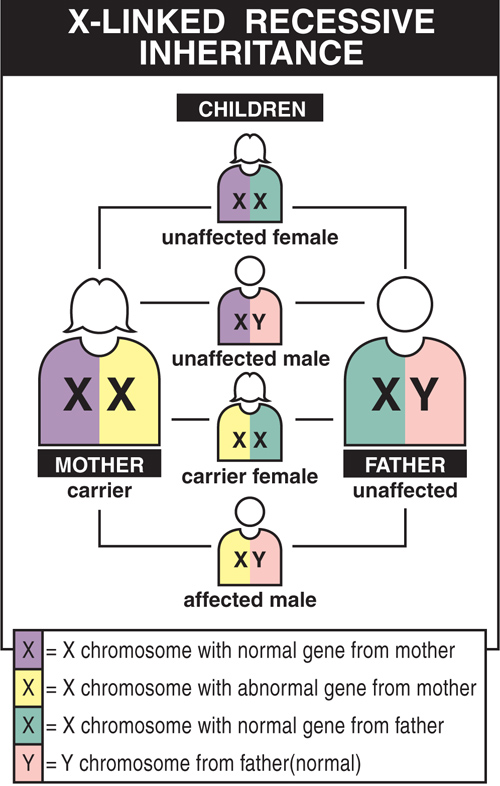

BMD is inherited in an X-linked pattern. That means the gene that sometimes contains a mutation causing these diseases is on the X chromosome.

Every boy inherits an X chromosome from his mother and a Y chromosome from his father, which is what makes him male. Girls get two X chromosomes, one from each parent. Each son born to a woman with a dystrophin mutation on one of her two X chromosomes has a 50% chance of inheriting the flawed gene and having BMD. Each of her daughters has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and being a carrier.

Carriers usually have no disease symptoms but can have a child with the mutation or the disease. BMD carriers are at risk for cardiomyopathy (see Signs and Symptoms).

How can a family with no history of BMD suddenly produce a child with the disease? There are two possible explanations:

- The genetic mutation leading to BMD may have existed in the females of a family for some generations without anyone knowing it. Perhaps no male children were born with the disease, or, even if a boy in an earlier generation was affected, relatives may not have known what disease he had.

- The second possibility is that the child with BMD has a new genetic mutation that arose in one of his mother’s egg cells. (Because this mutation isn’t in the mother’s blood cells, it’s impossible to detect by standard carrier testing).

If a mother gives birth to a child with BMD, there’s always the possibility that more than one of her egg cells has a dystrophin gene mutation, putting her at higher-than-average risk for passing the mutation to another child. Once the new mutation has been passed to a son or daughter, he or she can pass it to the next generation.

If a mother gives birth to a child with BMD, there’s always the possibility that more than one of her egg cells has a dystrophin gene mutation, putting her at higher-than-average risk for passing the mutation to another child. Once the new mutation has been passed to a son or daughter, he or she can pass it to the next generation.

A man with BMD can’t pass the flawed gene to his sons because he gives a son a Y chromosome, not an X. But he’ll certainly pass it to his daughters, because each daughter inherits her father’s only X chromosome. They’ll then be carriers, and each of their sons will have a 50% chance of developing the disease, and so on. A good way to find out more about the inheritance pattern in your family is to talk to your MDA Care Center physician or a genetic counselor.

For more information, see MDA’s booklet Facts About Genetics and Neuromuscular Diseases, and the 2012 video Genetics of BMD: Why Your Mutation Matters.

Females and BMD

Why don’t girls usually get BMD? When a girl inherits a flawed dystrophin gene from one parent, she usually also gets a healthy dystrophin gene from her other parent, giving her enough of the protein to protect her from the disease. Males who inherit the mutation get the disease because they have no second dystrophin gene to make up for the faulty one.

However, although girls don’t usually get the full effects of BMD, some females with the gene flaw are somewhat affected. A minority of females with the mutation are manifesting carriers, who usually have a mild form of the disorder.

For these women, a dystrophin deficiency may result in weaker muscles that fatigue easily in the back, legs, and arms. Some may even need a wheelchair or other mobility aids. Manifesting carriers may have heart problems, which can show up as shortness of breath or inability to do moderate exercise. The heart problems, if untreated, can be quite serious, even life-threatening.

A female relative of someone with BMD can get a full range of diagnostic tests to determine her carrier status. If she's found to be a carrier, regular strength evaluations and close cardiac monitoring can help her manage any symptoms that may arise. For asymptomatic carriers, it is recommended to repeat cardiac assessments every three to five years; however, for carriers who develop symptoms, it is recommended to go through more frequent cardiac assessments.3

References

- Takeshima, Y. et al. Mutation spectrum of the dystrophin gene in 442 Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy cases from one Japanese referral center. J. Hum. Genet. (2010). doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.49

- Darras, B. T., Program, N., Miller, D. T. & Urion, D. K. Dystrophinopathies - GeneReviews - NCBI Bookshelf. GeneReviews, Seattle (2018).

- Birnkrant, D. J. et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet. Neurol. (2018). doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30025-5