European Team Combines Stem Cells, Gene Correction to Treat DMD-Affected Mice

A European group of researchers successfully used a combination of genetic correction and stem cells to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in mice with the disease. The compound they used for the genetic correction was developed by Judith van Deutekom, then at Leiden (Netherlands) University Medical Center, with MDA support.

DMD results from the loss of the muscle protein dystrophin because of any of a number of genetic errors in the dystrophin gene.

Yvan Torrente at the University of Milan (Italy), Luis Garcia at the Institut de Myologie in Paris, and colleagues, who published their results Dec. 13 in Cell Stem Cell, corrected the genetic error in the DMD-causing gene in cells taken from patients with the disease and then used the corrected cells to treat DMD-affected mice.

The strategy is thought to have potential for treatment of human patients, although there are safety concerns.

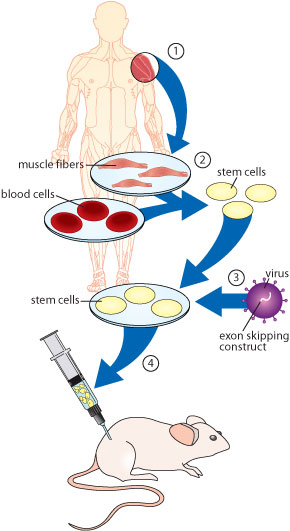

In their experiments, the investigators first extracted muscle-generating stem cells known as CD133-positive cells from both muscle tissue and blood in people with DMD.

They then corrected the genetic error in the cells’ dystrophin genes outside the body with a technique known as exon skipping.

They then corrected the genetic error in the cells’ dystrophin genes outside the body with a technique known as exon skipping.

This strategy blocks the part of the gene that contains an error, coaxing the cell to skip that part and produce a shortened, but still functional, dystrophin protein from the remaining genetic instructions.

When the researchers injected the genetically corrected stem cells into dystrophin-deficient, DMD-affected mice, either into an artery or into muscle tissue, they saw a significant recovery of muscle form and function and production of dystrophin. (The immune systems of the mice had been altered so that they could tolerate the human cells.)

The muscle-derived CD133-positive cells gave rise to better muscle regeneration than did the blood-derived cells. Injections into muscle and into an artery both led to muscle regeneration, but it was more widespread with the arterial injections.

“Our approach of using exon skipping for the expression of human dystrophin within the DMD CD133-positive cells should allow the use of the patient’s own stem cells, thus minimizing the risk of immunological graft rejection,” the researchers write.

But the main hurdle is that, with present technology, the exon-skipping compounds are delivered to cells using a virus that integrates into chromosomes. If the virus integrates into the wrong place, it could cause cancer or disrupt important genes.

Current MDA grantees who are working on exon skipping for the dystrophin gene are Stephen Wilton at the University of Western Australia in Perth; Howard Michael at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City; Gordon Lutz at Drexel University in Philadelphia; and Carmen Bertoni at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Related human testing

In December, in the journal Cell Transplantation, Torrente and colleagues announced they had transplanted CD133-positive stem cells taken from the muscles of eight boys with DMD back into the same patients from whom they had originally been extracted, with no observed adverse effects. No gene correction was involved.

And a phase 1 trial in the Netherlands recently tested an exon-skipping compound developed by the Dutch company Prosensa in boys with DMD. No stem cells were involved.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information