Help Today, Help Tomorrow is Goal of MDA's Duchenne Clinical Research Network

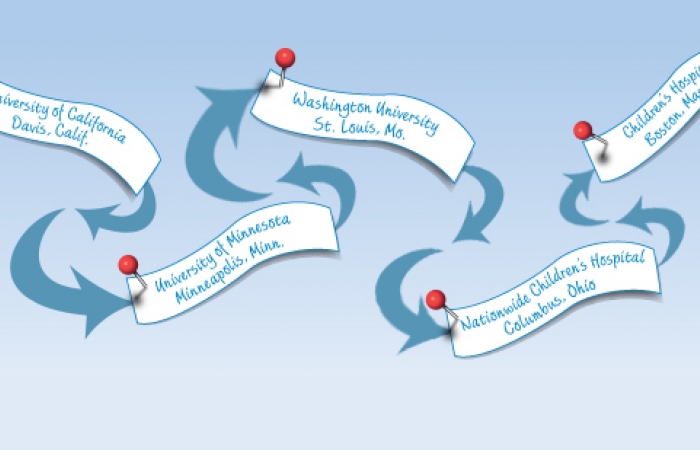

Update (June 16, 2014): As of June 2014, the following seven centers comprise the MDA DMD Clinical Research Network: University of California, Davis; Nemours Children's Hospital, Orlando, Fla.; Boston Children's Hospital; University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis; Washington University, St. Louis; Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; and Children's Medical Center of Dallas.

“There’s a lot of basic and clinical research going on in Duchenne now, and that’s exciting. We’re all eager for treatment strategies like exon skipping to work,” says John Day, director of the MDA Clinic at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“But at the same time, exon skipping is not available today, and I’m seeing patients in the clinic today.”

Making a difference right now in the lives of people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and their families is one of the goals of MDA’s DMD Clinical Research Network — at the same time as it is dedicated to improving and streamlining scientific research for the future benefit of these same individuals.

Day’s clinic is one of five in the network, which was established by MDA in August 2008. The others are: Children’s Hospital Boston; Washington University in St. Louis; Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio; and the University of California at Davis (UC Davis).

Living longer today

Living longer today

Bringing the DMD community together and making sure patients and caregivers know about the latest advances in clinical care is as much a goal of the network as coordination of research studies, Day says.

The network has helped Day and others organize several large and active regional conferences so that everyone in the DMD community — including clinicians, families, caregivers, physical and occupational therapists, and other health care providers — knows about and has access to the latest options for managing the disease and treating its symptoms.

“My model [for DMD] is cystic fibrosis,” Day explains. “It used to be that patients died of cystic fibrosis in their teens. Now they typically live into midlife, easily. And we still haven’t gotten a definitive treatment for the disease.

“Clinicians who work with muscular dystrophy have taken that to heart. It’s very much our goal to get Duchenne patients to the point where they live as long as possible, and have as active, fulfilling and independent a life as possible. With advances in technology, that goal is increasingly within reach.”

Treatments for tomorrow

In addition to helping health care providers communicate with each other and with DMD families about the latest advances in medical management, the network also is helping to accelerate research on various aspects of DMD clinical care. At least three multicenter studies are currently under way.

“The best studies and drug trials now demand multicenter sites,” says Anne Connolly of Washington University in St. Louis. Connolly is spearheading a study of infants and toddlers with Duchenne MD, as well as one of teenagers and adults who are no longer walking (nonambulatory). She hopes to establish accurate ways of measuring the strength and function of individuals in these traditionally hard-to-study populations, so more complete and consistent data can be obtained.

“Single-doctor and single-site trials are bad science, except for pilot studies,” Connolly adds. “Multicenter trials are now needed.”

Jerry Mendell at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio agrees. Mendell also is working through the network to conduct a study comparing the effects of two drugs, losartan and lisinopril, on hearts affected by DMD.

Jerry Mendell at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio agrees. Mendell also is working through the network to conduct a study comparing the effects of two drugs, losartan and lisinopril, on hearts affected by DMD.

“The study we’re doing would really be impossible in just a single center,” Mendell says, noting that there aren’t enough people in any one region of the country who meet the study criteria and are available to participate. “Without patient participation, we wouldn’t be able to do these studies. The network has really helped us reach out to these volunteers.”

Assembling a large study population through the network will enable researchers to collect enough data to begin to narrow down which patients are at higher risk for early heart problems and which symptoms are associated with conditions needing treatment.

Improving the process

The network also is benefiting DMD research by standardizing the procedures used by those conducting the studies. Mendell has organized several trainings of technicians conducting the heart-function tests to ensure they all employ the same techniques and use identical outcome measures. Echocardiographers from all five sites were brought to Ohio State University in Columbus for training.

“Cardiologists supervised them every step of the way for two days,” Mendell says. “They were checked for reliability. They had to achieve results within a 5 percent error rate or their site wouldn’t be allowed to enroll patients.”

“Cardiologists supervised them every step of the way for two days,” Mendell says. “They were checked for reliability. They had to achieve results within a 5 percent error rate or their site wouldn’t be allowed to enroll patients.”

Furthermore, Mendell’s team visited the five sites to address questions about the study’s double-blind, randomized control protocol, and make sure that there would be no problems with the pharmacies receiving and distributing the drugs at each site. “We developed a manual of operations that has been delivered to each site to address specific questions that may come up during the trial,” he says.

Setting up the heart study — the training, the site visits, the operations manual — has helped lay the groundwork for other studies utilizing the network.

Moreover, “the network has allowed us to develop the infrastructure for future clinical trials,” says Basil Darras, co-director of the DMD clinic at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

Mendell is planning a trial that will utilize the network to follow up on a small study on exon skipping at his clinic. “Once we have initial results from that [pilot] study, we’ll extend it to the other four sites as well,” he says, using similar protocols to those established for the heart study.

Rewriting ‘natural history’

One thing researchers are finding as they study people with DMD is that, because of improved care — in particular the widespread use of steroids — “people are losing skills at a much later age,” says Craig McDonald, co-director of the MDA Clinic at UC Davis.

“Getting up from the floor, walking, self-feeding, maintaining pulmonary function — we are having to redefine the expected natural history [disease progression] of people with DMD,” he says.

The wide reach of the clinical research network is helping physicians not only redefine but rewrite this natural history.

“If we can show that these treatments or interventions [such as steroids and ventilators] are slowing the rate of progression,” McDonald says, “then we have evidence of a therapeutic benefit” — a benefit that’s here today, ready to be shared with the entire DMD community.

For more information

Participants are currently being recruited for most of the trials mentioned in this story.

For information about the studies of infants and toddlers with DMD, as well as the study of older (ages 7 to 22) people with DMD who are nonambulatory, please contact Pallavi Anand at anandp@neuro.wustl.edu or (314) 362-2490.

For information about the losartan vs. lisinopril study, as well as a natural history study of heart function in people with DMD, contact Laurence Viollet at laurence.viollet@nationwidechildrens.org or (614) 355-2695.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information