The Heart of Care

When one partner is the primary caregiver for the other, a little creativity and a lot of communication help keep the fire burning

When a couple vows to share their lives — whether or not they express that commitment before an authorized officiant — there’s a traditional phrase that holds particular pertinence when one partner is both mate and primary caregiver for the other. It’s the line about loving one another for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health.

When caring for a partner with a neuromuscular disease, those words are often put to the test, especially in terms of intimacy. On the other hand, if both partners use the challenges to spark a little more laughter, sincere communication and resourceful creativity, these challenges can ignite and sustain a deeply intimate love.

The big picture

The first step, suggests Rebecca Axline, a supervisory licensed clinical social worker at Houston Methodist Neurological Institute, site of an MDA ALS Care Center, is for both partners to realize that they’re much like any other couple. “When one partner has a neuromuscular disease and the other partner is the caregiver, there will be role changes,” she says. “But that doesn’t make you different; that makes you normal.”

Couples deal with role changes all the time. The birth of a child, caring for an elderly parent, clashing work hours — all these situations change each partner’s role in a relationship and often leave little time for romantic intimacy. “I encourage individuals to recognize this and look at role changes as something that’s normal in every relationship,” Axline says.

“I’m not minimizing any aspect of neuromuscular disease, but understanding how ‘normal’ you and your partner are can be very freeing,” she adds. “Once you realize that everyone gets the rug pulled out from under them at some point or another, both partners are in a much better position to find creative, out-of-the-box solutions that can bring back the intimacy they crave.”

The new normal

The second step, particularly when one partner assumes the role of primary caregiver, is to redefine “normal” intimacy.

Scott Thomas, 27, received a diagnosis of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) in 2012. Thomas and his 24-year-old fiancée, Sarah Lidstrom, who is Thomas’ primary caregiver, see their situation as a “new normal.”

“Feeling romantic was very difficult early on,” Thomas says. “I had so many insecurities about what I could no longer do. For me, the solution was to stop focusing on what everyone calls a ‘normal romantic relationship’ and focus instead on what works for my partnership with Sarah. Once I did that, I learned that what Sarah needs most is to feel loved and cared for. That I can do!”

Expanding on Thomas’ outlook, Lidstrom emphasizes how important it is to accept that things will be different — but that doesn’t have to be negative. “The best thing we did for our relationship was to accept the fact that it was not going to be like when we first met or like the relationships we see around us. That doesn’t make us better or worse, just different,” she says.

“We are here for each other through anything life throws at us, and we are able to see the good that has come from all of this. We developed a passion for traveling and adventure; we make each other laugh like no one else can; and we realize that this hurdle has transformed us into the people we want to be. I don’t think we would be able to say all this had it not been for this disease process.”

As for finding intimacy in a relationship, Lidstrom adds, “If close contact is an important piece of intimacy for you, then find time for that during transfers or spend time lying next to each other in bed. If kissing is important, then kiss. It may be a kiss on the cheek, but that kiss can mean more than any other kiss you’ve ever had in your life. If sex is an important part of your relationship, be creative and figure out how to have sex. Just know that intimate experiences will be different. That doesn’t make the experiences less important. They may be more important, because you have to be a little more clever to get what you both need.”

Defining intimacy

A key to taking Lidstrom’s advice is to look at the true meaning of intimacy. “In our culture, we often equate intimacy with sex,” says Axline. “In reality, aspects of intimacy include intellectual and emotional connections.”

Axline adds, “When I talk to couples, I explain how intimacy uses all your senses — touch, smell and vision — as well as emotions, like caring and warmth. Intimacy is so much bigger than what we often see it as.”

Intimacy can be a gentle touch: Rickie, 62, and Dianne Bauer, 59, have been happily married for 41 years. After Rickie was diagnosed with ALS in 2012, the couple learned that intimacy is much bigger than they originally thought. “I think we’re luckier than some couples,” Dianne says. “After 41 years, we’re very comfortable with each other, and we’re best friends. So, yes, our intimate relationship has changed, but we naturally started communicating our love in new ways — warm hugs, holding hands, laughter and lots of little pecks on the cheek.”

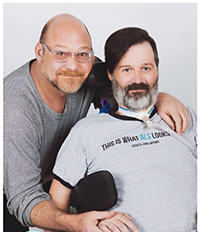

Intimacy can be a knowing glance: Some of life’s most intimate moments follow a deep, meaningful connection, whether verbal or nonverbal. If anyone understands that idea, it’s Ronald Thompson, 52, the primary caregiver for his partner Brian Fender, 48, who was diagnosed with ALS in 2011. Today, Fender has a tracheostomy to breathe, and he can no longer talk, walk, sit up, type or eat on his own. “We’ve been together for 24 years — 19 years before Brian’s diagnosis — so we have a level of communication that goes beyond anything any disease can throw at us,” Thompson says.

Without the power of speech, Thompson has learned to read Fender’s expressions. “He has a certain smile when he’s feeling frisky. It’s a glimmer in his eyes that’s impossible to resist. He’s just adorable. And his expressions tell me how he feels about household decisions, too, which he is always part of. He’s never excluded. That’s what keeps our relationship genuine and intimate. He’s not my patient; he’s an intimate member of our family,” Thompson says.

Intimacy can be open, heartfelt honesty: According to Lizz Barna and Joseph McCabe, honest communication — no holds barred — is a powerful element of intimacy. “Being able to completely trust someone is amazingly intimate,” Barna says.

Barna has lived with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) for nearly 33 years, since she was diagnosed at 18 months old. Her partner and primary caregiver is Joseph McCabe, now 44, and as he puts it, “I’m more in love with Lizz than ever.”

A profound part of that love stems from the fact that Barna was always honest about her disease. “I told Joe everything from day one,” she says. Both agree that knowing the facts allowed McCabe to make a conscious decision. Was he up to caring for this woman through better and worse, sickness and health? McCabe chose to stay by Barna’s side, which was, to say the least, an intimate choice, and it continues to drive their close, loving relationship. In fact, today the couple has a wonderful 11-year-old son.

Intimacy can be spontaneous giggles and grins: “Laughter is very important; it keeps us strong,” Dianne says, adding that Rickie likes to set up moments of levity by doing something unexpected, like making a fuss about the clothing his wife sets out for him in the morning. Rickie is not and has never been a fashionista, so this prompts Dianne to reply, “Are you kidding me?” And of course, he is kidding, which is apparent as Dianne watches Rickie sit there “smiling and giggling.”

Barna and McCabe couldn’t agree more. “You have to have a sense of humor — keep things light,” Barna insists. Whether it’s a major issue, such as when a piece of essential equipment goes awry, or a general inconvenience, like when Barna can’t reach her much-loved Snapple, she says there are two choices. “I can get angry and depressed, or I can laugh it off and move on. Obviously, there are times when Joe and I have to discuss serious matters, but overall, we think it’s a waste of time to spend life being angry and fighting.”

Making it work

It turns out that neuromuscular disease cannot delete intimacy between two lovers. It may take another form, but it’s always there if both partners are willing to work at it. As Dianne says, “Rickie and I worked on our marriage every day prior to his diagnosis, and we still work at it — we just work at it differently.”

Facing role changes is a normal part of every couple’s union. And when done with love, patience and creativity, it may very well turn out to be one of the better, richer, healthier times.

Donna Shryer is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Care for the Caregiver

When you’re the primary caregiver for a loved one, there’s no denying that the experience ranks right up there with life’s most meaningful, giving and often uplifting acts. At the same time, though, caregiving can be physically exhausting and emotionally draining.

Here are some tips on staying happy and healthy that benefit everyone involved.

1. Laugh it up

When caring for a loved one with neuromuscular disease, a little levity may help the caregiver get through what might otherwise be a tense situation. Studies suggest that laughing may turn on the brain’s endorphins — the same pain-relieving chemicals released in response to exercise, excitement and love, among others. Research also indicates that a hearty laugh may relieve physical tension and stress for up to 45 minutes after the laughter ends.

Find ways to exercise your sense of humor both with and without your loved one — watch comedies, share jokes with friends, or practice laughter yoga, which combines deep breathing and calming movement with interactive laughter exercises.

2. Indulge in self-indulgence

Ronald Thompson, the primary caregiver for his partner Brian Fender, who has ALS, brings up a strong argument in favor of caregivers tending to their own physical, mental and emotional needs. “It’s tough to feel intimate when I’ve barely slept and put off getting a haircut, bathing or even getting dressed. And I’m not talking about sex. Cuddling, kissing, holding hands or resting in bed next to Brian — these are intimate moments, too. And it helps when I feel attractive.”

So as a caregiver, Thompson’s advice is to take care of your physical health, but never underestimate the importance of “feeling pretty.”

3. Find outside help

“When I talk to someone caring for a partner with neuromuscular disease, I stress trying to hire private help as early as possible and often as possible,” explains Rebecca Axline, a supervisory licensed clinical social worker at Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. To accomplish the feat, which can admittedly be challenging, Axline advises asking your MDA Care Center team, including the social worker, neurologist, nurse and family support and clinical care coordinator, about what resources are available. Another resource is your local MDA office. To help cover out-of-pocket expenses, some couples put together GoFundMe accounts or ask their place of worship to host a fundraiser.

Thank You, Caregivers!

MDA would like to recognize all the family caregivers whose tireless support and devotion help empower people living with neuromuscular diseases and ensure they receive the care they need. From MDA, we say thank you. MDA is here to provide help, support and hope to families whenever, wherever they need us. To find caregiver resources, visit mda.org/services/caregiver-resources.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information