Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS)

Causes / Inheritance

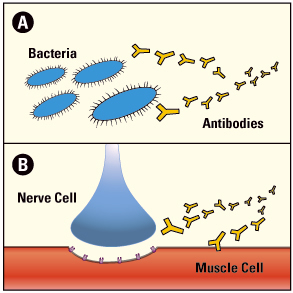

The immune system normally defends the body against diseases, but sometimes it can turn against our own body, leading to an autoimmune disease. LEMS is one of many autoimmune diseases, which include rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes. People with LEMS without cancer may have other autoimmune diseases. In all of these diseases, an army of immune cells and antibodies that would normally attack disease-causing bacteria and cancer cells mistakenly attacks cells and/or proteins that have essential functions in the body.

The immune system normally defends the body against diseases, but sometimes it can turn against our own body, leading to an autoimmune disease. LEMS is one of many autoimmune diseases, which include rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes. People with LEMS without cancer may have other autoimmune diseases. In all of these diseases, an army of immune cells and antibodies that would normally attack disease-causing bacteria and cancer cells mistakenly attacks cells and/or proteins that have essential functions in the body.

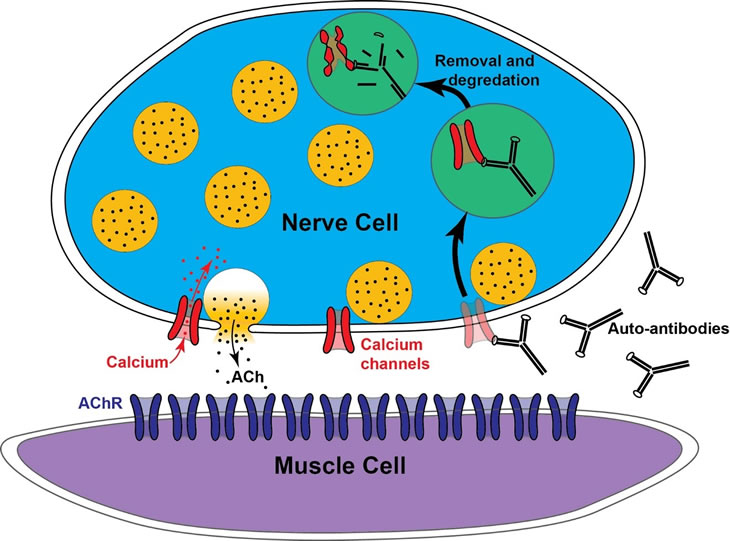

At the normal neuromuscular junction, a nerve cell tells a muscle cell to contract by releasing the chemical acetylcholine (ACh). First, an electrical spike (action potential) in the nerve triggers the opening of voltage-gated calcium channels allowing calcium ions to enter the nerve terminal. These calcium ions bind to a protein on ACh-containing vesicles, triggering the release of ACh.

ACh diffuses to the muscle cell and binds to ACh receptors (AChRs). This allows an inward flux of electrical current that triggers muscle contraction. These contractions enable someone to move a hand, dial the telephone, walk through a door or complete other voluntary movement.

At the ending of the motor nerve, electrical activity normally opens calcium channels (red) that allow calcium ions to enter the nerve ending and trigger the release of acetylcholine (ACh) contained in vesicles (yellow circles). LEMS occurs when the immune system makes antibodies that selectively attack calcium channels. This leads to their internalization and destruction. As a result, in LEMS there are fewer calcium channels at nerve endings, leading to a reduction in ACh release and resulting muscle weakness.

While myasthenia gravis (MG) targets the ACh receptors on muscle cells, LEMS targets voltage-gated calcium channels on the nerve endings, interfering with ACh release.

The trigger for LEMS without cancer is unknown, but may have a genetic component linked to autoimmunity. Approximately 85-90% of people with LEMS test positive for autoantibodies against the P/Q subtype of voltage-gated calcium channel, which are enriched at the nerve endings (presynaptic terminals) of motor neurons that control muscle contraction. These autoantibodies bind to the calcium channels, leading to their internalization and functional loss. This results in fewer available calcium channels leading to less calcium entry during nerve activity, and ultimately reduced ACh release. When ACh release falls below the threshold required to trigger muscle contraction, muscle weakness occurs.

In LEMS cases associated with small cell lung cancer, it is believed that the cancer cells make P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels, similar to those found on motor neurons. The immune system recognizes the cancer cells as a threat and generates antibodies against cancer cell proteins, including the tumor-associated calcium channels. However, these antibodies also recognize the same channels on motor neurons, resulting in an attack on the nerve terminal and subsequent LEMS symptoms.

All people with LEMS are tested for antibodies against calcium channels. While most test positive, a small percentage are “seronegative,” meaning no detectable calcium channel antibodies are found. These individuals may have antibodies to other proteins involved in ACh release. In fact, most people with LEMS likely have antibodies targeting multiple nerve terminal proteins. Additionally, some people test positive for calcium channel antibodies without showing signs of LEMS (see LEMS Diagnosis), possibly due to low antibody levels.

Additional reading

- Kesner VG, Oh SJ, Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ. Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2018 May;36(2):379-394. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.01.008. PMID: 29655456; PMCID: PMC6690495.

- Varon MC, Dimachkie MM. Diagnosis and treatment of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Practical Neurology (US). 2024;23(3):26-28,47.

Last revised December 2025.