Myasthenia Gravis (MG)

Causes/Inheritance

What causes myasthenia gravis (MG)?

The immune system normally defends the body against diseases, but sometimes it can turn against the body, leading to an autoimmune disease. MG is just one of many autoimmune diseases, which include arthritis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes.

The immune system normally defends the body against diseases, but sometimes it can turn against the body, leading to an autoimmune disease. MG is just one of many autoimmune diseases, which include arthritis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes.

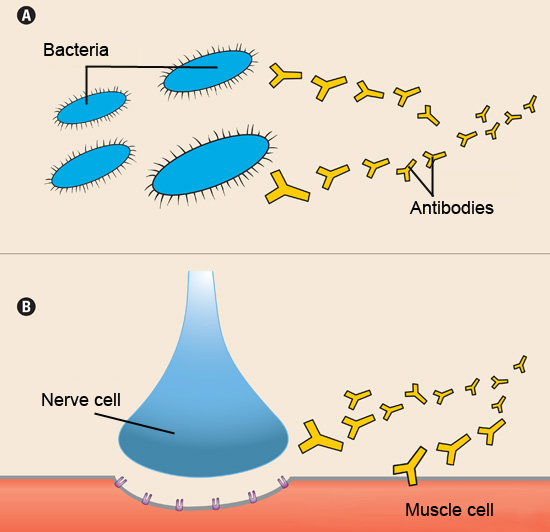

In all these diseases, an army of immune cells that would normally attack bacteria and disease-causing "germs" mistakenly attacks cells and/or proteins that play an essential role in the body. In most cases of MG, the immune system targets the acetylcholine receptor — a protein on muscle cells that is required for muscle contraction (see illustration to the right).

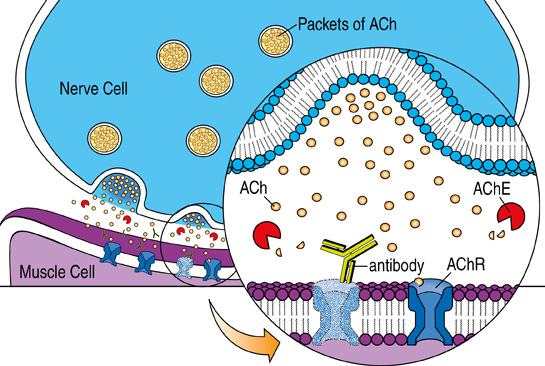

At the normal neuromuscular junction, the nerve ending releases the chemical acetylcholine (ACh) leading to muscle contraction. ACh attaches to the ACh receptor — a pore or "channel" in the surface of the muscle cell — twisting it open and allowing an inward flux of electrical current that triggers muscle contraction. These contractions enable someone to move a hand, to dial the telephone, to walk through a door, or to complete any other voluntary movement.

About 85% of people with myasthenia gravis (MG) have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) in their blood. These antibodies—Y-shaped proteins produced by immune cells called B cells, which normally target bacteria and viruses—mistakenly attack and destroy many of the AChRs on the muscle membrane. With repeated nerve stimulation, as occurs with continued muscle use, the amount of acetylcholine (ACh) released by the nerve decreases. As this release declines, the remaining functional AChRs in individuals with MG are less likely to be activated, leading to muscle weakness. This is why patients with MG typically experience worsening muscle weakness with prolonged activity. In some cases, the immune attack is severe enough to cause persistent, constant symptoms.

About 85% of people with myasthenia gravis (MG) have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) in their blood. These antibodies—Y-shaped proteins produced by immune cells called B cells, which normally target bacteria and viruses—mistakenly attack and destroy many of the AChRs on the muscle membrane. With repeated nerve stimulation, as occurs with continued muscle use, the amount of acetylcholine (ACh) released by the nerve decreases. As this release declines, the remaining functional AChRs in individuals with MG are less likely to be activated, leading to muscle weakness. This is why patients with MG typically experience worsening muscle weakness with prolonged activity. In some cases, the immune attack is severe enough to cause persistent, constant symptoms.

Scientists do not know what triggers most autoimmune reactions, but they have a few theories. One possibility is that certain viral or bacterial proteins mimic "self-proteins" in the body (such as the AChR), stimulating the immune system to unwittingly attack the self-protein.

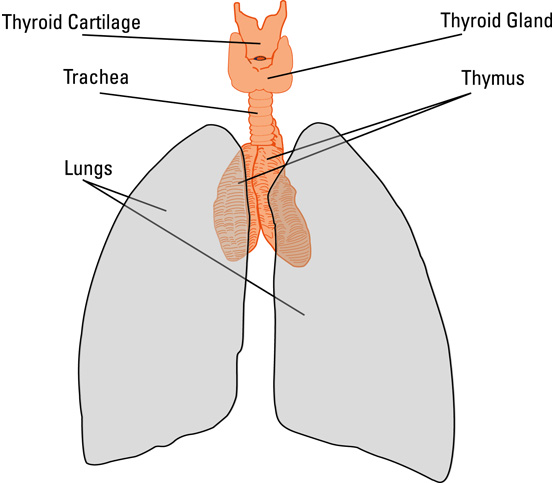

There's also evidence that an immune system gland called the thymus plays a role in MG (see illustration below). Located in the chest just below the throat, the thymus is essential to the development of the immune system. From fetal life through childhood, the gland trains immune cells called T cells to distinguish self from non-self.

About 15% of people with MG have a thymic tumor, called a thymoma, and another 75% have thymic abnormalities, a condition called thymic hyperplasia. When the thymus does not work properly, the T cells might lose some of their ability to distinguish self from non-self, making them more likely to attack the body’s own cells.

About 15% of people with MG have a thymic tumor, called a thymoma, and another 75% have thymic abnormalities, a condition called thymic hyperplasia. When the thymus does not work properly, the T cells might lose some of their ability to distinguish self from non-self, making them more likely to attack the body’s own cells.

What is the genetic susceptibility in MG?

Although MG and other autoimmune diseases are not hereditary, genetic susceptibility does appear to play a role. It seems likely that genetic factors also contribute to the pathogenesis of MG. Certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types, cell-surface proteins that are responsible for the regulation of the immune system, have been associated with MG, including HLA-B8, DRw3, and DQw2. MuSK antibody-positive MG is associated with haplotypes (clusters of genes inherited together) DR14 and DQ5.

Most studies suggest that if people have a relative with an autoimmune disease, their risk of getting an autoimmune disease is increased — the closer the relative, the higher the risk.

Even for identical twins, however, that risk is relatively small. Most studies suggest that when one twin has an autoimmune disease, the other has less than a 50% chance of getting the same disease.

Also, people who already have one autoimmune disease have a greater risk of developing another one. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of people with MG have another autoimmune disease that appeared before or after the onset of MG. The most common of these are autoimmune thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (a disease that affects multiple organs).

Additional reading

- Kaminski HJ, Sikorski P, Coronel SI, Kusner LL. Myasthenia gravis: the future is here. J Clin Invest. 2024 Jun 17;134(12):e179742. doi: 10.1172/JCI179742. PMID: 39105625; PMCID: PMC11178544.

Last reviewed June 2025 by Neelam Goyal, MD.