One Day at a Time

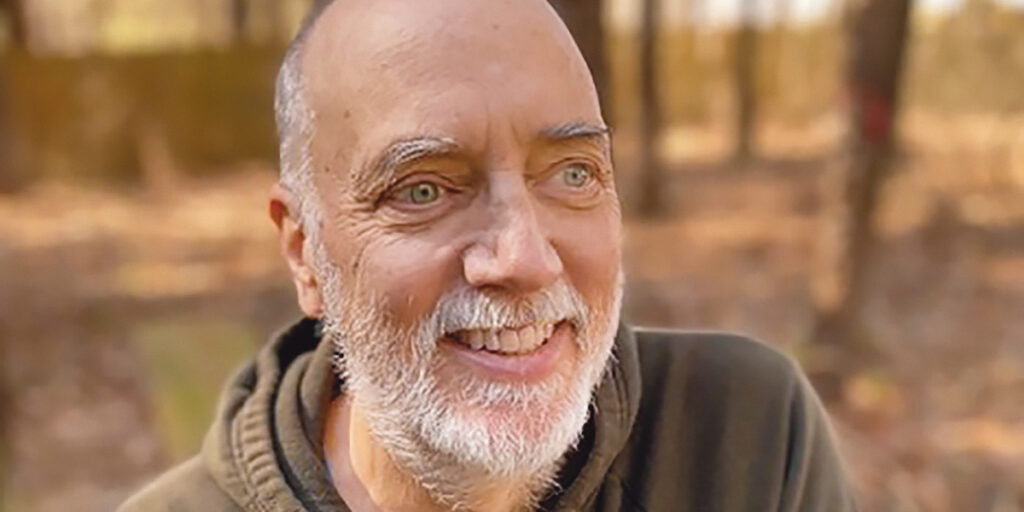

By Thaddeus Dombrowski | Friday, May 13, 2022

Being diagnosed with myotonic dystrophy changed my life, and I had to change with it

On my 28th birthday, I recognized that something was wrong. I used to be able to jump and touch the rim of a basketball hoop. But on this day, I was missing by a foot.

I remembered learning in a high school science class that a sudden loss of athleticism was a sign of a neuromuscular problem, but I didn’t want a medical diagnosis altering my plans. So, I decided to shut it out of my mind until it became a real concern.

Altering plans

Fast forward 21 years. I was a software engineer in Arizona, and I was riding my bicycle to work, as I had been doing a few times a week for years. I loved biking, which I had taken up to strengthen my legs. But, on this day, as I locked my bike to the rack at work, my body spoke to me. In my mind I heard it say, “You are not biking anymore. I can’t do this.” And that was that. I still wanted to ride my bike, but my body refused.

For several years I had been keeping a journal. Lately, I found myself struggling to find words to describe what I was experiencing. Something was not right, but, until the day of my last bike ride, I didn’t even know what to tell my doctor. Finally, I made an appointment. I told her about that ride and the pain I was experiencing.

At first, I was given a clinical diagnosis of motor neuron disease. In 2012, I was surprised when a genetic test revealed that I actually have myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2).

Advancing symptoms

Three months later, I needed a cane to walk. In medical literature, DM2 is described as mild, so I figured the cane would be the end of the story.

At work, I had accumulated a lot of sick pay. I started taking an occasional day for rest. It wasn’t long before I needed a rest day each week. Then, it was twice a week.

Outside of work, life was becoming impossible. Dirty dishes were piled in the sink. My house was filthy. I was exhausted. I finally recognized that this was untenable. A year after my diagnosis, I declared for disability.

Within another year, I needed a wheelchair. But things began to turn around after I got into an MDA Care Center. A sleep study led to a diagnosis of central sleep apnea, which is common with DM2. I started using a bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine, and for the first time in years, I began to sleep through the night.

Adapting to change

The year before this ordeal began, my wife and I separated. I wanted to continue to live independently, but I needed to be closer to my family. My older sister and my mom live in North Carolina. I told them that I wanted to move near them, but I couldn’t give an ETA. I was just learning to adapt to my new reality, and there was so much to do.

The prospect of moving was daunting. However, by planning everything out and breaking things into achievable tasks, I made progress.

One of the first problems was finding a wheelchair accessible van. I turned to the internet to begin my search, but I knew nothing and really needed someone to talk to. I visited a mobility dealership and found that they were exactly the people to help me. They invited me to participate in a disability support group at the dealership, after hours. They also matched me with a used van within my budget.

Making a move

It took two more years until I was ready to move. To pull this off, I rented an apartment near my home and brought everything I wanted to keep to the apartment. What was left in the house was stuff to sell or give away. Then I put the house on the market. At this point, I could finally leave for North Carolina.

I rented while I was house hunting. I had no expectation of finding a home equipped for me, but I studied each option and considered the accessibility hurdles. In 2017, almost a year after moving here, I bought a home. After having a ramp and front deck built, I finally moved into my new home.

Now, five years later, I remember the effort it took to change my life, but also the attitudes and beliefs that needed to shift. For example, my first response to my diagnosis was simply to push harder. I didn’t know what else to do. But, when I finally accepted that I have a disability, I stopped being so hard on myself. I began to listen to my body and to rest more between activities. Now, I think things through more before doing them. The goal is to work smarter, not harder. I also had to become more patient and forgiving of myself and others.

Since I made these changes, I am happier and more optimistic than I have been in years. Acceptance, patience, and self-forgiveness have led me to a new confidence about my situation.

Thaddeus Dombrowski was diagnosed with myotonic dystrophy (DM) in 2012. He lives with his two cats in North Carolina, where he raises worms to support his gardening habit.

TAGS: Ambassadors, Featured Content, From Where I Sit, Staying Active

TYPE: Featured Article

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.