The Search for Inclusion Body Myositis Treatment

By MDA Staff | Friday, December 4, 2020

Inclusion-body myositis (IBM) is one of the most common disabling inflammatory myopathies in older adults, but its underlying cause is poorly understood.

IBM is characterized by progressive muscle weakness and wasting. In patients with the disease, inflammatory cells invade muscle tissue and collect between the muscle fibers. Muscle biopsies of patients diagnosed with IBM reveal multiple “inclusion bodies” containing cellular material of dead tissue.

To learn more about IBM, we spoke with neurologist Anthony A. Amato, MD, who has headed the MDA Care Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston since 1999. Dr. Amato is considered one of the nation’s top experts on IBM and other inflammatory myopathies.

What exactly is IBM, and how common is it?

IBM is probably the most common inflammatory muscle disease in people older than 50, if you don’t include sarcopenia, which is age-related. IBM is frequently underdiagnosed, but its prevalence is between 5 and 10 per 100,000 — and it’s a little more common in men than in women. We don’t know of any ethnic or environmental risk factors, though there is an association with some other autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis and Sjøgren’s syndrome.

What’s the prognosis for people with IBM?

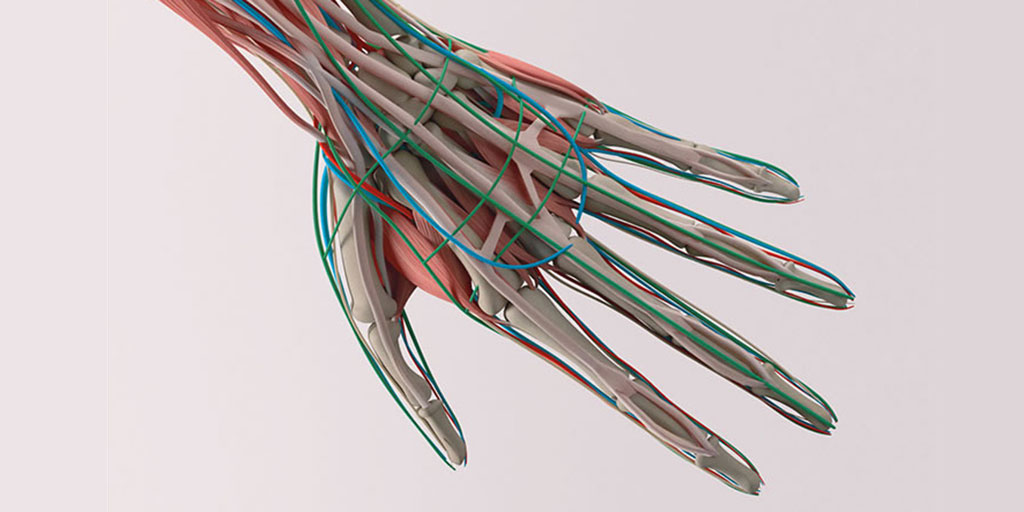

IBM progresses slowly, typically starting in the hands, but there can be variations. For most people, initial symptoms are difficulty climbing stairs, getting out of a chair, and walking long distances — activities that all rely on the quadriceps. People also have a hard time grasping objects, holding a pen, buttoning their shirts, or opening jars. These are early signs of IBM, which is different than what you might find in other types of myositis. In the other types, lifting the arms over the head is affected, while in IBM, it’s the fingers that are affected. It’s also more asymmetric, affecting patients more in one arm or leg than the other.

In most cases, symptoms start after the age of 60, but some patients may start in their 40s, and I’ve seen it even in the late 30s in patients with HIV. But it’s a debilitating, progressive disease, so within 10 or 15 years, patients may be in a wheelchair. About 60% of patients also develop swallowing problems, and some need a feeding tube.

How did you become so involved with this disease?

IBM is a huge part of what I see at our Care Center. It’s a big clinic, and we may see 25 patients a week with IBM; I have 50 or more whom I actively follow. Back in 1991, I did my fellowship with Jerry Mendell, MD [currently a neurologist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio], and he had a very strong interest in IBM. I was there at the time he published his landmark paper demonstrating the presence of amyloid deposits in the muscle fibers of patients with IBM. That sparked my interest.

Are there any effective treatments for IBM?

Not at this time. I generally refer patients for physical and occupational therapy and, if they have swallowing problems, speech therapy. Patients have tried various immunotherapies, prednisone, methotrexate, and intravenous gamma globulin, but these all have side effects, and in randomized trials, they haven’t been shown to be effective.

What about clinical trials?

Right now, Orphazyme is doing a trial of arimoclomol involving 100 patients in the United States and 50 in England. The hypothesis is that it increases heat-shock protein production in the muscle, reducing the formation of inclusions. Most of the patients in this 20-month study will finish in the next six months, and we look forward to seeing the results.

There are also efforts to develop antibodies that target some of the specific inflammatory cells seen in the bloodstream and muscle of people with IBM. That holds a lot of promise.

What can people with IBM do today to help advance research?

There are research studies underway that involve donating blood and muscle tissue. If IBM patients are going to have a diagnostic muscle biopsy, they can elect to donate the leftover tissue to research.

They can also volunteer for clinical trials. We don’t have a difficult time recruiting patients; they really want to participate in these studies because options for treating IBM are limited.

Advancing Research

MDA supports 150 research projects worldwide. Learn more about how we are working to accelerate the delivery of treatments and cures at mda.org/science.

TAGS: Clinical Trials, Healthcare, Research, Research Advances, Resources, Spotlight

TYPE: Featured Article

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.